Policy Update

Jayasree

Background

The Korean wave, etymologically known as the hallyu, refers to the soft power of the Korean popular culture that originated in Southeast Asia, first in mainland China and eventually spreading across Asia in the late 1990s. The transnational cultural influence of the K-wave in the postmodern era is one of a kind due to the decisive yet dominant nature of ‘compressed modernity’. South Korea experienced a century’s worth of economic growth-led cultural influence within the span of a few decades. The phenomenon of ‘Miracle on the Han River’ transformed a war-ravaged South Korea that was one of the 25 poorest countries in the world in the 1960s into an advanced economy built on technology and innovation, with the help of the International Development Association of the World Bank.

(Source: Korean Antique Furniture)

Hallyu emerged at a time when the unambiguously contested interpretations of Sino-centricism in the East Asian region had almost entirely shifted from Orientalism to military hard power in exerting its geopolitical influence. This disintegrated the Chinese tributary system that held significance as a cultural hegemon in the ancient Silk Route-led politics before the era of Eurocentric world order.

The Korean-style development model was anchored by a state-developed capitalism that equipped Korean politico-economy ideologies to be cultural missionaries with economic returns. The magnanimity of Hallyu was predicted by China by its perception of Hallyu as a cultural mania.

The hallyu is of four waves that include hallyu 1.0 (Korean drama/movies), hallyu 2.0 (K-pop music), hallyu 3.0 (K-culture) and hallyu 4.0 (K-style). The multidimensional economic scope of hallyu is backed by the state investment due to a promising return of investment.

K-wave in India

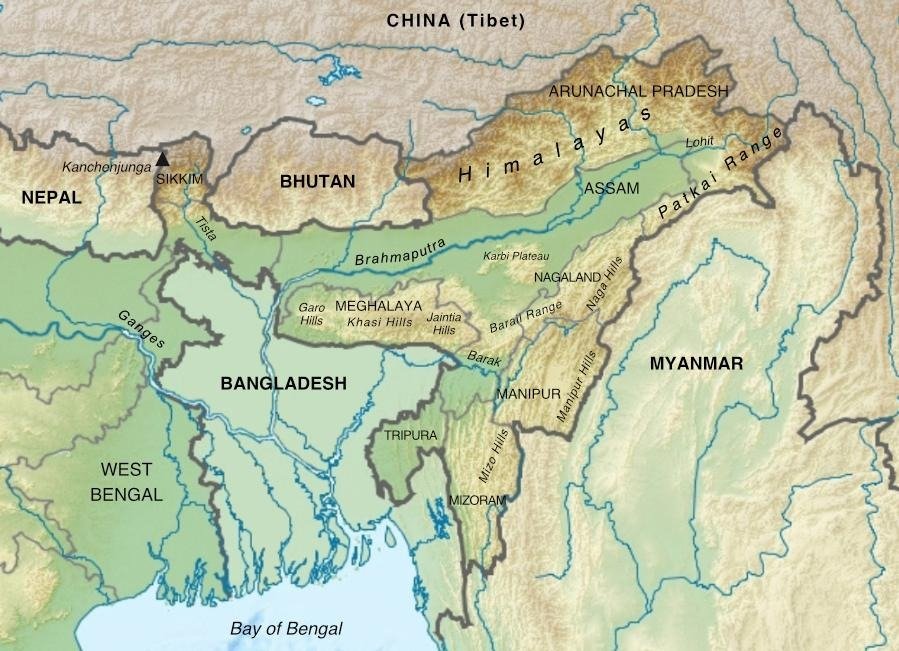

(Source: Q-files)

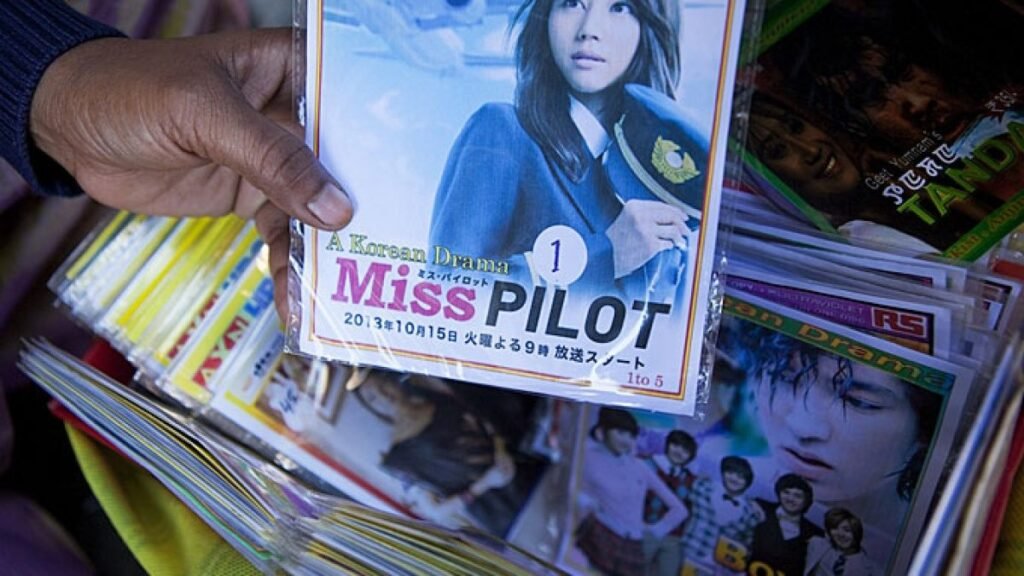

In India, hallyu first made its way into the northeastern region in the late 1990s due to its geopolitical proximity with China and the cost-effective accessibility to pirated DVDs of Korean media. It gained momentum in Manipur in 2000 when the Revolutionary People’s Front of Manipur had banned Hindi films and Hindi satellite channels as a protest to Indianisation and the threat of Manipuri cultural erosion. The Arirang TV of Korea and the access to pirated media from the Indo-Myanmar border town of Moreh had culturally invaded Manipur.

(Source: Al Jazeera)

The Korean dramas and movies were aesthetically, culturally and economically aspirational to the viewers who had been used to the dominance of Bollywood narratives that were not inclusive of the traditional and cultural values of ‘the seven sisters of India’. Over the next two decades, Hallyu ascended in its cultural influence in India and across the world due to globalisation, the emergence of social media super-national fandoms, and the growth of online streaming services and OTT.

K-wave’s Global Emergence

The hallyu spread to the world from East Asia through the Middle East to the West. The emergence of pop-music bands such as Girl Generation (since 2007), BTS (since 2010) and Blackpink (since 2016) shaped K-pop in the global scenario. The virality of Psy’s ‘Gangnam Style’ in 2012 and ‘Parasite’ (2019) being the first foreign film to win an Oscar for best feature raised the stakes for Korean media. This pushed it from the peripheries of world media to mainstream.

(Source: Indiatimes)

Hallyu is not a mere compulsive imitation of the Western media; it was a perfect glocalisation of cross-cultural consumption. It held the eastern traditional values as well as solid western capitalist aspirations, giving rise to a phenomenon of ‘bilateral hallyu’, where countries of the world try to find a cultural common ground with Korean culture to be included in the mainstream cultural influence.

The cultural and economic manifestations of Hallyu

South Korea is ranked 12th overall in the Global Soft Power Index 2025 out of more than 100 countries. It ranks 9th globally in the “Culture & Heritage” pillar and 7th in “Arts and Entertainment” (Brand Finance Global Soft Power Index). It ranks as the 13th-largest economy in the world and the 4th-largest economy in Asia by nominal GDP as of 2025. It has a projected share of 500 billion USD in the creative economy of the world, which is approximately 1.5 trillion USD, with forecasts predicting growth to USD 800 billion by 2033.

(Source: The Political Economy of Development – WordPress.com)

India-South Korea bilateral soft power

India and Korea are two non-warring nations of the global south that are emerging regional leaders with a good command over their soft power and smart power. The legend of the Ayodhya princess of the ancient Gaya Kingdom marrying Korean King Kim Suro (Kimhae/Gimhae region), their rich linkage of Dravido-Korean languages, the culinary and gastronomic parallels and ancient records of maritime trade are a few historic testimonials of their bilateral soft powers. These cultural linkages are fundamental in the dynamic modern geopolitics.

India’s Soft Power Ceiling

Indian culture, media, cuisine and wellness lifestyle have been a soft power for world nations. India’s Bollywood movies and dramas are famous among non-Indians across Central and West Asia, Africa, and the West. The growing Indian diaspora have always been cultural brand ambassadors bridging foreign state actors.

(Source: Center for Soft Power)

However, this soft power does not have the impact of the Korean wave because of the lack of an ethnocentric idea of a diverse India, the perception of it as a centre of exoticism and mysticism, its non-aspirational economic power, stereotypical tokenism in mainstream Western media, and the complex cultural identities and disputed demographic identities of Indians. India is therefore looked upon as a mere populous market of consumption by world countries. India’s Soft Power ceiling prevents the permeability of its culture consumption into the west and eventually to the rest of the world.

Way Forward

For India to strengthen its soft power capacity and create a strategic cultural equilibrium with South Korea, a recalibration of its cultural diplomacy and creative economy is essential. The Korean state’s innovation-orientated, export-driven policy plays a superior role in the order of its commercial business.

The loopholes in its policies on the publicity-related commercial laws facilitate the hyper-realistic aspirations promoted by the K-culture idols. India can learn from Korea on how institutional investments in media, digital arts, design, and entertainment sectors can yield economic as well as diplomatic dividends.

(Source: 38 North)

India has a great scope in leveraging the bilateral Hallyu phenomenon to start joint ventures with South Korea with the help of bilateral cultural centres as well as commercial entertainment houses. The use of digital diplomacy, influencer networks, and youth partnerships must be institutionalised to revitalise India’s soft power efforts that are limited to academic partnerships, student exchange programmes, art programmes and cultural council events.

References

Akoijam, S. (2012). Korea comes to Manipur. The Caravan, 4(5). https://caravanmagazine.in/reviews-and-essays/korea-comes-manipur

Chang, P.-L., & Lee, H. (2017). The Korean Wave: Determinants and its impact on trade and FDI. Retrieved from https://economics.smu.edu.sg/sites/economics.smu.edu.sg/files/economics/Events/SNJTW2017/Hyojung%20Lee.pdf

Kim, B.-R. (2015). Past, present and future of Hallyu (Korean Wave). American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 5(5), 154–160. https://www.academia.edu/download/118235049/Past_Present_and_Future_of_Hallyu_Korean.pdf

Oviya AJ. (2021, October 29). Tamil Nadu and Korea: An untold tale of princess Sembavalam. The ArmChair Journal. https://armchairjournal.com/tamil-nadu-and-korea-sembavalam/

Presidential Committee on New Southern Policy. (2020). Republic of Korea: New Southern Policy information booklet. Retrieved from https://apcss.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Republic_of_Korea-New_Southern_Policy_Information_Booklet.pdf

Qin, Y. (2018). A multiverse of knowledge: Cultures and IR theories. The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 11(4), 415–434. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/poy015

How South Korea became a cultural power and what happens next. (2025, June 21). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/21/world/asia/south-korea-kpop-culture.html

The Observatory of Economic Complexity. (n.d.). South Korea (KOR) exports, imports, and trade partners.https://oec.world/en/profile/country/kor

Pirie, I. (2008). The Korean developmental state: From dirigisme to neo-liberalism. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203944653

About the Contributor

Jayasree is a research intern at IMPRI (Impact and Policy Research Institute), and is currently pursuing her bachelors in political science from Madras Christian College, Chennai.

Acknowledgement: The author sincerely thanks Aasthaba Jadeja and IMPRI fellows for their valuable contribution.

Disclaimer: All views expressed in the article belong solely to the author and not necessarily to the organization.

Read more at IMPRI:

Fixing the Future: How a Feminist Just Transition Can Deliver Real Climate Solutions

Silent Waves: Feminist Reflections on Maritime Security and the Women, Peace & Security (WPS) Agenda