Event Report

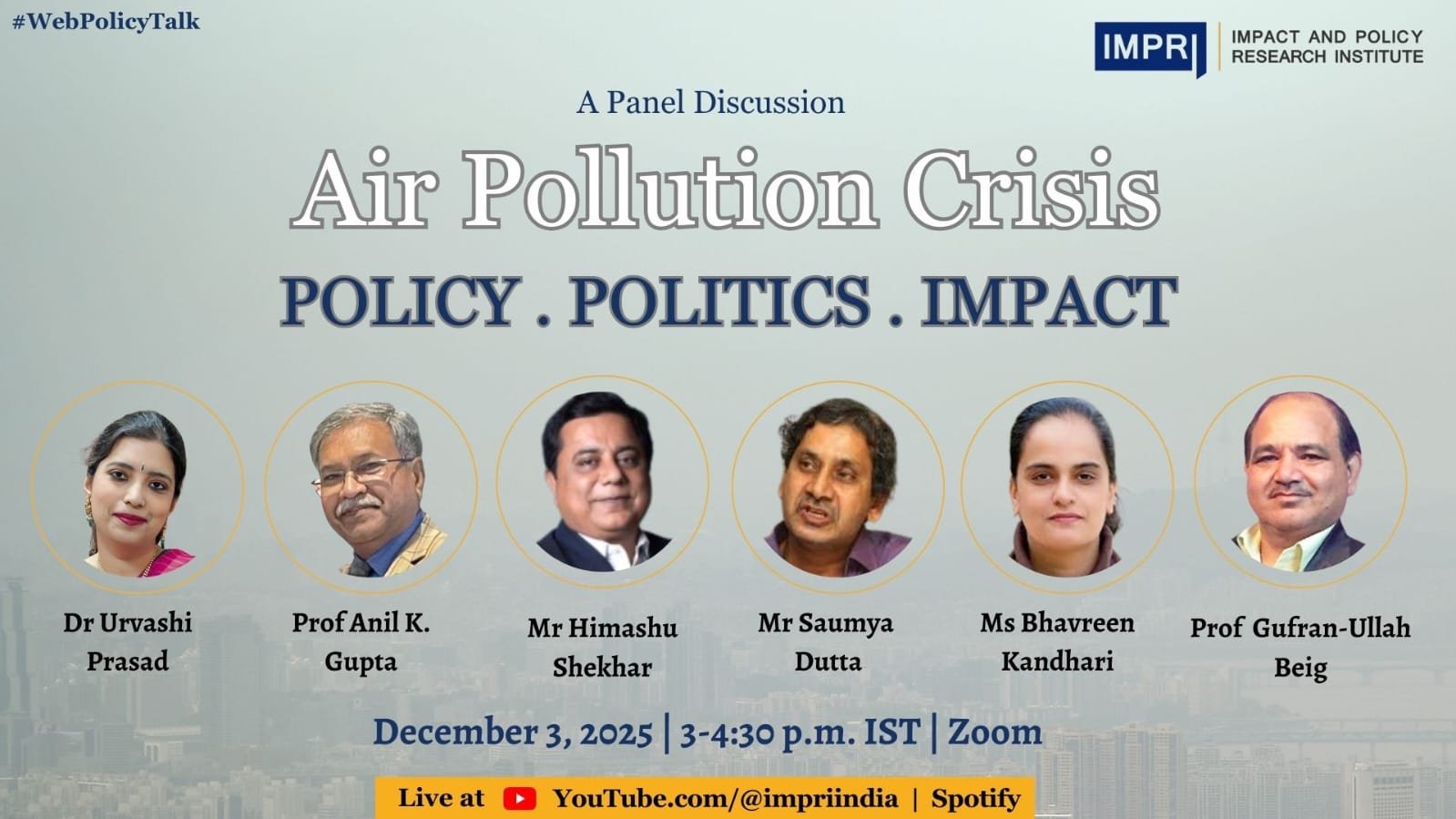

Organiser: IMPRI Centre for Environment, Climate Change and Sustainable Development, IMPRI Impact and Policy Research Institute, New Delhi

Date: 3 December 2025

Format: #WebPolicyTalk — Panel Discussion (Zoom | YouTube Live | Spotify)

The panel discussion on “Air Pollution Crisis: Politics, Policy and Impact,” organized by the IMPRI Centre for Environment, Climate Change and Sustainable Development, brought together experts, practitioners, and policy analysts. They examined India’s worsening air pollution emergency from scientific, political, economic, and public health angles.

Dr Urvashi Prasad, Former Director, Office of Vice Chairman, NITI Aayog, New Delhi; Visiting Senior Fellow, IMPRI. The panel included Dr. Gufran-Ullah Beig, Chair Professor, National Institute of Advanced Studies (NIAS), (IISc); Founder Project Director, System of Air Quality and Weather Forecasting And Research (SAFAR); Mr. Himanshu Shekhar, Senior Editor at NDTV; Mr. Soumya Dutta, Founding co-convener, SAPACC (South Asian People’s Action on Climate Crisis); Former Advisory Board member, UN Climate Technology Centre & Network; Visiting Senior Fellow, IMPRI; and Prof. Anil Kumar Gupta, Professor & Chief Executive, Integrated Centre for Adaptation to Climate Change, Disaster Risk Reduction and Sustainability ICARS, IIT Roorkee.

The discussion drew on real-time data, long-term trends, source apportionment studies, and the lived experiences of residents. It explored why India still faces severe air quality issues despite years of policy efforts and what structural, scientific, and political changes are necessary to tackle this crisis.

Throughout the session, speakers highlighted a combination of governance failures, fragmented responses, scientific gaps, inequity issues, and the political neglect of air pollution as contributing factors to the crisis. The discussion emphasized that air pollution in India is now a nationwide public health emergency, not just limited to Delhi or the winter months.

In her opening remarks, Dr. Urvashi Prasad described the crisis as one that goes beyond environmental issues and impacts public health, economic productivity, and overall human well-being. Drawing from her own experience of developing non-smoker’s lung cancer due to toxic air exposure, she stressed that the crisis is personal, urgent, and widespread. She pointed out the increasing number of “new hotspots” appearing beyond the Delhi NCR region, including areas in North India and even Mumbai, where AQI levels have been persistently poor.

Dr. Prasad also highlighted the political aspect of the crisis. She argued that air pollution will continue to be a low priority for policymakers unless it becomes a major electoral issue. She noted that even though public outrage happens every winter, political action remains seasonal and reactive. Without ongoing pressure from citizens and strong political commitment, she warned that the crisis cannot be effectively addressed.

Scientific Foundations and Data Integrity: Insights from Dr. Gufran-Ullah Beig

Dr. Gufran-Ullah Beig provided a detailed scientific explanation of why India’s air quality management is still lacking. He emphasized that air quality policy should focus on health, but India’s actions remain scattered, under-scientific, and heavily driven by administrative convenience rather than scientific accuracy.

He pointed out major flaws in India’s monitoring system. Although Delhi has one of the best sensor networks in the country, the placement of air quality stations is not based on sound science. Many stations are located either too close to gardens, which leads to underestimating pollution, or too near traffic corridors, which results in overestimating pollution. International guidelines suggest a proportional distribution across different environments, something India does not have.

Dr. Beig emphasized that the Indian system still depends on old mitigation guidelines. Many of these were created over ten years ago and have not been updated based on new atmospheric science. For example, the country ignores the impact of secondary pollutants. This includes secondary PM2.5, which forms through chemical reactions between nitrogen oxides (NOx), volatile organic compounds, and ammonia when exposed to sunlight. These secondary pollutants can make up 30 to 40 per cent of Delhi’s PM2.5 load during certain seasons, but they receive little focused policy attention.

Dr. Beig also stressed the need for a change to the airshed approach, arguing that pollutants do not respect administrative boundaries. Delhi’s pollution cannot be reduced without including nearby states such as Haryana, Punjab, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh, because atmospheric transport constantly moves pollutants across these regions.

Regarding seasonal patterns, he explained that stubble burning has a significant impact for only a short 40-day period, with spikes in contribution reaching up to 22% on specific days. However, when looking at the entire year, its impact lowers to 3–8%. Thus, the broader crisis arises from year-round sources, mainly vehicular emissions, dust, construction activities, and secondary pollutants, not just crop burning.

He criticized the dependence on outdated guidelines and called for the establishment of a central scientific body to consistently update standards and policies according to changing climate and weather conditions.

Media, Politics and Public Discourse: Intervention by Mr. Himanshu Shekhar

From the perspective of political reporting, Mr. Himanshu Shekhar highlighted the increasing political awareness of air pollution. He noted that, surprisingly, several members of Parliament called for a debate on air pollution on the very first day of the winter session. Some MPs even wore air-purifying masks inside Parliament to make a point.

Mr. Shekhar presented data on AQI trends from Diwali over the past five years to show slight improvements in some years and also data on stable burning in Punjab and Haryana, showing a decline by more than 50 %. However, he warned that these changes should not hide the deep-rooted issues causing the crisis.

He also pointed out the impact of weather changes, mentioning that shifts in wind speeds, winter inversions, and climate-related changes worsen air quality. Interviews with meteorologists indicated that wind speeds in Delhi-NCR during pollution peaks are consistently low, which increases stagnation and traps pollutants closer to the ground.

Another major point in Mr. Shekhar’s talk was how reactive India’s policy response is, especially regarding the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP). He noted that GRAP is put into action only after pollution has reached crisis levels. This makes it a reactionary, after-the-fact procedure instead of a way to prevent problems. By the time construction stops, traffic limits are put in place, or industrial activities are reduced, the public has already faced long exposure to toxic air. He questioned whether a framework based on emergency responses can truly deal with a chronic, structural issue.

From his position as a senior journalist, he also discussed the media’s role in shaping public discussion. He observed that while media attention spikes during severe pollution events, it stays quiet for the rest of the year. In truth, he stressed, data shows that Delhi and many other Indian cities often have unhealthy air quality for much of the year. They frequently exceed national and international standards, even in non-winter months. He argued that ongoing coverage is crucial for building long-term political pressure.

Lastly, he emphasized the growing number of new air pollution hotspots in areas that were once considered relatively clean, including parts of western and southern India. This trend indicates that pollution is no longer just a problem for Delhi-NCR but a national crisis driven by infrastructure growth, urbanization, transportation demands, and climate change. His remarks highlighted that this issue is systemic, affecting multiple cities and sectors. It requires not just occasional outrage but a consistent national conversation based on scientific understanding and political will.

Structural and Social Dimensions: Contributions by Mr Soumya Dutta

Mr. Dutta began by addressing a persistent public and political narrative: the tendency to exaggerate stubble burning as the main cause of Delhi’s pollution every winter. He referenced five different studies on source apportionment. According to these studies, stubble burning accounts for only 3 to 8% of Delhi’s PM burden annually. Even during the peak 40 to 45-day harvesting period, it becomes a major contributor only on a few specific days, reaching peaks of 20 to 45%. Outside this time frame, Delhi’s air remains hazardous due to other factors. He urged the audience to distinguish between short, dramatic seasonal spikes and the steady year-round baseline, which stems mostly from urban and industrial sources.

He reiterated that the main source of PM2.5 and PM10 in Delhi comes from vehicle emissions. These contribute not only to particulate matter but also to secondary pollutants like ground-level ozone and nitrogen oxides. He argued that as long as the transport sector continues to grow without significant reform, meaningful improvements in air quality will not happen. Road dust and construction dust are the second and third largest contributors. They fluctuate with the seasons but consistently remain major sources.

A key scientific point Mr. Dutta raised was the lack of a strong winter inversion at the time of his discussion. Typically, cold air traps pollutants near the ground during the winter. However, this year, warmer temperatures and higher winds prevented this inversion from forming. Nevertheless, pollution levels stayed severe, indicating that the crisis cannot be attributed solely to weather conditions or agricultural fires from outside.

Another significant issue he addressed was the cross-border transfer of pollutants, especially from coal power plants in nearby states. Delhi has mostly closed its coal plants, but states in the NCR region continue to operate theirs. The prevailing seasonal winds carry these emissions into Delhi-NCR, showing that local actions alone cannot solve the crisis.

Mr. Dutta also looked at the often-ignored impact of the aviation sector. He explained that aircraft engines burn aviation turbine fuel, which is essentially kerosene, much less efficiently than car engines. Because takeoff and landing happen at low altitudes with poor dispersion, airports create concentrated pollution hotspots. He added that India’s policy of reducing train services while promoting aviation is “a policy against the climate.” Aviation has a carbon footprint 6 to 8 times greater per passenger-kilometre compared to efficient train travel. He argued that these policy missteps deepen the underlying causes of pollution.

A powerful part of Mr. Dutta’s talk focused on environmental and social justice. He criticized the stark inequality in exposure and protection. Wealthy individuals can shield themselves with indoor air purifiers and HEPA filter air conditioners. In contrast, millions of vulnerable workers—street vendors, rickshaw drivers, sanitation workers, construction labourers, and porters—breathe toxic air for 8 to 12 hours daily. He described this situation as “extreme injustice,” highlighting that those who contribute the least to emissions are the most affected. He urged policymakers to include marginalized voices in air pollution governance and to ensure that solutions do not disproportionately impact the poor.

He strongly criticized what he called “cosmetic governance responses,” such as spraying water near monitoring stations to artificially lower recorded AQI levels. He explained that these practices reduce public trust and distort the true severity of the crisis, especially as millions now own personal sensors that reveal real-time discrepancies.

Mr. Dutta also pointed out broader policy and ecological risks. He stressed that the Supreme Court’s recent narrow, unscientific definition of the Aravalli hill range threatens the ecological barrier that historically reduced dust and particulate transfer into Delhi. Increased quarrying and stone-crushing in the Aravallis will further destabilize this natural protective wall and worsen air quality for many years.

In conclusion, he emphasized the difference between pollution levels and exposure. He explained that AQI numbers alone do not capture the full extent of harm; what truly matters is how much pollution people actually breathe. Exposure varies based on occupation, movement patterns, economic class, time spent outdoors, and access to protection. Therefore, public health must be at the forefront of air policy, not just emission control or AQI monitoring.

Ecosystems, Agriculture and Land-Use Dynamics: Reflections by Prof. Anil Kumar Gupta

Prof. Anil Kumar Gupta provided a vital ecological, agricultural, and land-use perspective to the discussion. He emphasized that we need to understand air pollution not just through emissions but also by looking at broader changes in landscapes and climate. He pointed out the increasing climate-induced changes in cropping cycles across North and Central India. Rising temperatures, erratic rainfall, and unpredictable monsoon patterns have altered sowing and harvesting times in Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and even Madhya Pradesh. These changes shorten harvesting timelines, often forcing farmers to quickly clear fields through burning, which worsens seasonal spikes in pollution.

He noted that traditional mulching and soil-enriching practices have declined. This is partly due to fertilizer subsidy structures and mechanization, which have left more crop residue on fields. Without proper incentives for alternative uses, farmers often choose burning as the cheapest option.

Prof. Gupta raised a significant and often overlooked issue regarding Delhi’s shifting vegetation profile. He explained that the spread of species like Prosopis juliflora (kikar) changes microclimates by releasing water vapour during winter mornings. This extra moisture interacts with pollutants when winds are light, making smog worse. He stressed that urban forestry policies should consider the impacts of various species rather than focusing only on increasing the number of trees.

A major governance issue he addressed was the lack of collaborative research. Many scientific studies exist on agriculture, dust, aerosols, vegetation, weather, and urbanization, but policymakers continue to rely on isolated findings. Prof. Gupta advocated for creating regional knowledge groups that bring together environmental science, agriculture, public health, climate studies, and disaster management to develop a comprehensive long-term air quality strategy.

Conclusion

The session ended with acknowledging that India’s air pollution crisis results from overlapping scientific, political, ecological, and social issues. The panel’s views showed that we can no longer look at this problem through single-blame stories or temporary actions. Instead, it requires a major change in how the country sees, manages, and reacts to toxic air.

Ultimately, the discussion highlighted that tackling air pollution is not just an environmental duty but also a social necessity. It needs a team of scientists, policymakers, journalists, citizens, and institutions working together with ongoing commitment. The speakers emphasized that this crisis cannot wait for the next winter to spark political action. The change must start now, based on science, focused on justice, and rooted in our shared duty to ensure clean air for everyone.

Acknowledgement: This report was written by Ayush Verma, a research intern at IMPRI