Policy Update

Madhu Swaraj

Background

Despite the Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act (PEMSR Act, 2013) legally banning the dehumanizing practice of manual scavenging in India, the crisis persists. Deadly accidents during sewer and septic tank cleaning tragically demonstrate the failure of implementation, showing that this decades-old scourge remains a fatal reality.

Taking this matter into consideration, the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (MoSJE) in convergence with the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) launched the National Action for Mechanised Sanitation Ecosystem (NAMASTE) scheme in July 2023. The scheme is to be implemented with an outlay of Rs. 349.70 crore, over the three-year period up to 2025-26, in all 4800+ Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) of the country.

The primary objective of the NAMASTE scheme is to ensure the safety and dignity of the Sewer and Septic Tank Workers (SSWs). It aims to prevent manual hazardous cleaning and enhance the occupational safety of the workers via capacity building and access to improved machines and safety gears.

Functioning

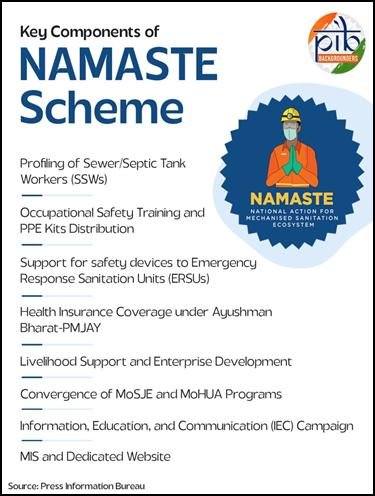

The NAMASTE scheme functions through a multi-pronged strategy, and the key components are as follows;

- Worker Identification and Profiling: The SSWs, and subsequently the Waste Pickers, are first issued occupational photo ID cards. The profiling and enumeration of the SSWs into the formal system is the first step towards formal recognition.

- Occupational Safety and Training: For workers to transition from manual cleaning to complete mechanisation, extensive occupational safety training is mandatory. They are also equipped with Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) kits, which include masks, body suits, gloves, and safety goggles.

- Social and Health Security: Identified SSWs and their families are being covered under the Ayushman Bharat-Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB-PMJAY), thus ensuring access to healthcare insurance.

- Livelihood and Mechanisation Support: The SSWs and their dependents, or Self-Help Groups (SHGs), are provided with financial assistance by the National Safai Karamcharis Finance & Development Corporation (NSKFDC). Sanitation-related vehicles and equipment can be procured with the help of this funding (capital subsidy and interest subsidy on loans), thereby facilitating their transition into ‘Sanipreneurs’ (sanitation entrepreneurs).

- Emergency Response and Institutional Capacity: In order to strengthen the on-ground infrastructure for safe and effective mechanised cleaning, the Emergency Response Sanitation Units (ERSUs) are established and capacitated within the ULBs. To ensure that even challenging cleaning tasks can be performed safely following prescribed protocols, these ERSUs are equipped with modern safety devices and equipment.

- Awareness and Convergence: Massive Information, Education, and Communication (IEC) campaigns must be conducted, aimed at changing public behaviour and increasing the demand for certified, safe sanitation services. The NAMASTE scheme makes it mandatory to hire services from registered and skilled sanitation workers/agencies by enforcing strict Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for sewer and septic tank cleaning.

Through the integration of these key components, the NAMASTE scheme systematically addresses the inherent risks, economic vulnerability, and lack of social security faced by the sanitation workers, and thus moves towards a truly mechanised sanitation ecosystem.

Performance

The NAMASTE scheme’s performance is assessed based on its ability to formalise the workforce, promote mechanisation, and provide a social safety net.

- As of late 2025, over 90,494 SSWs across the country have been successfully validated under the NAMASTE scheme. Giving SSWs a formal identity and a unique NAMASTE ID is the first crucial step for accessing all welfare benefits.

- Waste Pickers play a critical role in the urban sanitation chain and thus, over 42,127 Waste Pickers were validated and brought under the NAMASTE scheme’s safety net in June 2024.

- To ensure crucial financial protection against health crises associated with their hazardous work, over 68,341 SSWs and their families have been brought under the Ayushman Bharat-PMJAY or equivalent state health schemes.

- To enforce safe cleaning protocols, over 84,077 PPE kits have been distributed to SSWs, and over 555 Safety Device Kits have been issued to ERSUs.

- To promote the concept of ‘Sanipreneurs’, the SSWs and their dependents are being linked to financial support. In order to procure sanitation-related equipment, over ₹23.06 Crore Capital subsidies have been disbursed to over 769 sanitation workers, thus facilitating their shift from manual labour to business ownership.

- To provide skill upgrading and occupational safety training, over 1,112 workshops have been conducted, certifying workers to operate modern sanitation machinery.

Impact

The NAMASTE scheme plays a crucial role in the transition process of sanitation work, from hazardous manual labour to a dignified, mechanised, and skilled profession. Its impact can be measured primarily across three dimensions:

1. Social Inclusion and Dignity: Through formal recognition and social security, the scheme has profoundly impacted the marginalized and often stigmatized workforce. The scheme directly addresses the Right to Life (Article 21) by providing health insurance access to a population that is highly vulnerable to physical injuries, infections, and respiratory diseases due to occupational hazards. Extensive IEC campaigns are being conducted to change the public perception of sanitation work.

2. Economic Empowerment: Entrepreneurship and skill-based wages are being promoted to change the economic landscape for sanitation workers. The SSWs are provided with financial assistance to purchase modern sanitation vehicles and equipment, such as desludging vehicles and jetting machines.

3. Technological Adoption: The scheme has fundamentally altered the technology and processes used in urban sanitation. The ban on manual scavenging (under the PEMSR Act, 2013), combined with the financial incentives, has forced the ULBs and private contractors to invest wisely in the modern mechanised equipment, such as robotic cleaners and advanced camera inspection systems. The ERSUs within the ULBs have been provided with Safety Device Kits and specialized training and thereby reinforcing institutional responsibility for worker safety.

The NAMASTE scheme is a holistic intervention that impacts the entire socio-economic identity of sanitation workers, and not just job safety, thus setting a powerful precedent for inclusive urban development. The scheme’s lasting impact can be ensured through mechanisation, formalization, and convergence.

Emerging Issues

Despite its promising goals, the NAMASTE scheme has been grappling with several critical emerging issues. The zero-fatalities objective of the scheme is being undermined due to continued illegal use of informal human labor, which results in the stubborn persistence of fatalities in sewers and septic tanks. Furthermore, ‘Sanipreneurs’ are economically vulnerable as they compete against the low costs of illegal manual labor and also struggle to secure bank loans. This threatens the financial sustainability of their mechanised enterprises. Lastly, the problem is aggravated by institutional and data gaps.

Way Forward

The NAMASTE scheme is a transformative step in the right direction towards ensuring the safety and dignity, of the sanitation workers and Waste Pickers in India and their socio-economic empowerment.

The scheme should prioritize shifting from identification and entitlement distribution to rigorous, multi-agency enforcement. There should be 100% mechanization in order to achieve the zero-fatalities goal. The public investment must be accelerated for full deployment of city-appropriate mechanised equipment, including super-sucker vehicles and robotic cleaners, across all the ULBs. There must be simultaneous development of localised technical expertise for their maintenance.

Furthermore, the financial viability of ‘Sanipreneurs’ must be ensured by the government. This can be achieved by simplifying loan procedures and providing them access to long-term remunerative work contracts, which would enable them to compete against informal labor. Lastly, transparent monitoring and swift legal action would ensure the dignity and right to life of sanitation workers.

References

- Department of Social Justice and Empowerment. (n.d.). National Action for Mechanised Sanitation Ecosystem (NAMASTE) – Launch year 2023-24. Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India. https://socialjustice.gov.in/schemes/37

- National Safai Karamcharis Finance and Development Corporation (NSKFDC). (n.d.). NAMASTE. Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India. https://nskfdc.nic.in/en/content/home/namaste

- Press Information Bureau, Government of India. (2025, August 20). National Action for Mechanised Sanitation Ecosystem (NAMASTE) Scheme [Press release]. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2158328

- Press Information Bureau, Government of India. (2025, September 10). National Action for Mechanised Sanitation Ecosystem (NAMASTE): Empowering sanitation workers for safety and dignity [Press release]. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressNoteDetails.aspx?NoteId=155183&ModuleId=3

- Press Information Bureau, Government of India. (2025, October 9). Distribution of sanitation kits and Ayushman Cards under NAMASTE Scheme [Press release]. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2176763&hl=en-IN

About the Contributor:

Madhu Swaraj is a Research Intern at IMPRI.

Acknowledgement: The author extends sincere gratitude to the IMPRI team for their expert guidance and constructive feedback throughout the process.

Disclaimer: All views expressed in the article belong solely to the author and not necessarily to the organization.

Read more at IMPRI:

India-Bhutan: Hydro-Electric Trade and Future Prospects

Pradhan Mantri Janjati Adivasi Nyaya Maha Abhiyan (PM-JANMAN)